A space shuttle lost and extreme safety

This past February marked 14 years since the loss of Space Shuttle Columbia and her crew of seven astronauts over the skies of Texas. At the time I was working as a Federal On-Scene Coordinator with EPA Region 6 in Dallas.

This past February marked 14 years since the loss of Space Shuttle Columbia and her crew of seven astronauts over the skies of Texas. At the time I was working as a Federal On-Scene Coordinator with EPA Region 6 in Dallas.

Around 0800 that morning I heard a loud “boom,” which in my line of work usually means a gas explosion or similar. Waiting a few minutes and hearing no alarms or sirens, I flipped on the TV to catch some morning news. To my surprise all channels were showing the disintegration of Columbia. The coverage was so thorough because the return path of each mission is publicized ahead of time, and TV crews set up cameras to watch it pass over on its way to Florida.

I called the EPA Operations Center in Dallas to see whether we might be involved in any recovery operations. The consensus of our group and oth

Columbia Break-up

er agencies was that (a) nothing would make it to ground and (b) the military would likely be in charge. Wrong

on both counts.

As it turned out, despite breaking up at over Mach 18 (nearly 14,000 miles per hour), we would find a debris trail extending 220 miles from Dallas to western Louisiana. The cloud of falling debris was so dense that it was being tracked by weather radar and looked like a storm front.

Within hours of hitting the ground, shuttle parts were for sale on eBay, and reports were coming in of pieces all over southeast Texas. Because of the hazardous materials on board (i.e., rocket fuel), NASA immediately advised the public to avoid contact with the debris. Once the response was declared by the President to be an emergency, EPA became the lead agency.

I was deployed, along with another FOSC, to Lufkin, TX to establish our Disaster Field Office. We arrived to find numerous other agencies and support teams coming together for what was soon to become the largest interagency emergency mobilization in U.S. history.

Before the mission ended, 22,000 personnel from over 400 organizations would search 2.5 million acres, including over 680,000 acres shoulder-to-shoulder on the ground, recovering 40% of Columbia and all seven of the crew. The search is really the rest of this story.

Before the mission ended, 22,000 personnel from over 400 organizations would search 2.5 million acres, including over 680,000 acres shoulder-to-shoulder on the ground, recovering 40% of Columbia and all seven of the crew. The search is really the rest of this story.

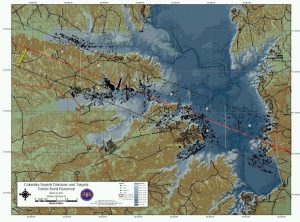

My first operational focus was on Toledo Bend Reservoir, the 185,000-acre lake running north and south between Texas and Louisiana. Hundreds of “ear witnesses” fishing a bass tournament in early morning fog heard debris raining down across the lake. What makes this lake so special for fishing is the forest of long-ago-flooded pine trees extending above the surface. That is also what made it extremely hazardous for search operations. I secured the Navy “SUPSALV” team to bring in the world’s best underwater search and recovery talent. Even with the best technology in existence at the time, Toledo Bend proved to be perhaps the most technically difficult search environment they had ever tackled.

Aside from the underwater blanket of trees that could easily impale boats and ensnare divers, the lake was murky (visibility one foot), had swift currents, was difficult to access  and suffered frequent late winter and early spring storms, whitecaps and sub-zero wind-chill. The entire area had a nearly complete lack of cell phone coverage and when warm weather finally arrived, so did the alligators. By April 12 the lake operation had conducted over 3,000 dives without injury, and I will take this opportunity to repeat my congratulations to Captain Jim Wilkins, USN (Ret) for his outstanding leadership of that operation.

and suffered frequent late winter and early spring storms, whitecaps and sub-zero wind-chill. The entire area had a nearly complete lack of cell phone coverage and when warm weather finally arrived, so did the alligators. By April 12 the lake operation had conducted over 3,000 dives without injury, and I will take this opportunity to repeat my congratulations to Captain Jim Wilkins, USN (Ret) for his outstanding leadership of that operation.

Back on land, searchers were battling their share of hazards. The first week gave us warm and pleasant enough weather, but later came tornados, an ice storm and eventually, torrential spring rains. We were strip-searching hundreds of map grids and documenting every piece of debris with latitude and longitude, photos and a unique ID number.

Finding 82,000 pieces, many smaller than a coffee cup, required aggressive and intimate contact with the land and the things that live there. Machetes and axes were standard issue, and it seemed that when the “piney woods” started to green up, everything with teeth and stingers came in force. Our people were immersed in terrain filled with hornets, yellow-jackets, scorpions, rattlesnakes, poison ivy, thorns, feral dogs and hogs, chiggers, ticks and, near water, alligators and water moccasins (more formally known as the Western Cottonmouth). Heat stress and dehydration just made it worse.

The alligators were relatively well behaved, but not so the rattlesnakes. As warm weather set in, field personnel had to be issued snake chaps – stiff leggings above the boot designed to stop fangs. Well-entrenched Timber rattlers took great offense at our intrusions, and at the peak of the search we were recording over 1,000 strikes (fangs hitting boots or chaps) per day. Amazingly no one actually got bit.

The alligators were relatively well behaved, but not so the rattlesnakes. As warm weather set in, field personnel had to be issued snake chaps – stiff leggings above the boot designed to stop fangs. Well-entrenched Timber rattlers took great offense at our intrusions, and at the peak of the search we were recording over 1,000 strikes (fangs hitting boots or chaps) per day. Amazingly no one actually got bit.

The safety side of this operation was very complex, not just because of the hazards I’ve described, but also because everyone was working at maximum capacity with no regard to fatigue management, and many of the personnel were not from the area. Briefings with crews coming in from New England frequently ended with long, disbelieving stares and questions like “What’s a chigger?” and “How fast can alligators run?” (faster than you). Native American firefighters from the western U.S. told us often that they were used to covering ground like this AFTER the fire and not dealing with thorny and often poisonous greenery and pests. In the skies air operations were going hard and fast, trying to cover as much ground as possible during daylight hours and before emerging greenery made it impossible to see what might have come to rest there.

This was a massive operation, and thousands worked tirelessly to do anything they could to accomplish the mission. As is often the case with emergency responses, safety was a focus, but it was constantly in jeopardy of coming in second (or third). Frankly it often did. But this kind of work is inherently unsafe, and during disasters Safety Officers must try to define and hold the line against what seems “unacceptably” hazardous.

Who decides how close I can come to an alligator? Should 1,000 rattlesnake strikes per day have caused us to terminate search activities? How about returning from a space mission and entering Earth’s atmosphere at 20,000 miles per hour in a largely aluminum and ceramic tile vessel? Some food for thought when you do your next JHA.