Help Wanted: IMT anywhere, anytime for as long as it takes

If you have been watching the news for the last several years, it’s obvious that disaster response is not going away. Events are getting larger, more complex and more expensive, as is the demand for qualified people to manage them.

In May and June of 2015, I supported the USDA as Deputy Incident Commander for their Avian Influenza response in Iowa. After tens of millions of dead chickens and turkeys, months of extended deployments and a billion dollars, that response finally wrapped. It was by far the largest, most complex and most expensive bird flu response in Agency history, affecting over a dozen states and severely testing USDA resources. Lessons learned ranged from managing the logistics of thousands of responders across 15,000 square miles to technical challenges of bio-containment, depopulation of sites with up to 10 million birds, disposal of the remains and returning these facilities to service (how do we know it’s clean?). They may need that knowledge again: scenarios for potential future outbreaks range up to five times what we did, putting the bar at perhaps a $5 billion event and even more prolonged deployments and impacts to the economy.

We saw a comparable challenge play out that year with wildfire responses in the western United States. Alaska lost 3.1 million acres, “an area the size of Connecticut”, to fire in July. By mid-August, the U.S. Forest Service reported that 30,000 firefighters and additional staff were deployed, the largest number in 15 years, “and it’s still not enough.” Then came the frank admission that the fires had exceeded the resources of the United States to fight them.

With over eight million acres gone, and counting, military units were being called up and firefighters were brought in from as far away as Australia and New Zealand. There was little optimism that losses in 2015 would not surpass the record 9.9 million acres burned in 2006, and indeed the final toll came in at 10 million acres. Hitting an unprecedented $243 million in one week, the Forest Service warned, “Fire seasons are growing longer, hotter, more unpredictable and more expensive every year, and there is no end in sight.”

In disaster management world, these are “Type 1” responses, which FEMA defines as “the most complex, requiring national resources for safe and effective management and operation.” Type 1 events by definition will often exceed 1,000 responders and related personnel during the operational period, usually 24 hours, and many events are far larger. The 2003 Shuttle Columbia recovery, at that time the largest interagency emergency response ever mounted in the United States, saw 5,000 on any given day during the height of the response. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon response peaked at around 50,000 responders. Our Iowa Bird Flu operation reached nearly 3,000 personnel.

The U.S. Fire Administration defines an IMT (Incident Management Team) as “a comprehensive resource (a team) to either enhance ongoing operations through provision of infrastructure support, or when requested, transition to an incident management function to include all components/functions of a Command and General Staff.” In simple terms, these personnel fill the boxes at the top of the response structure and are the key decision makers and managers of the expanded operation, including the Safety Officer role.

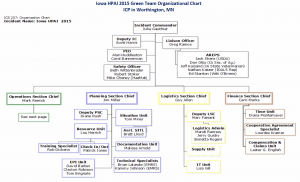

Few, if any, agencies have the internal personnel and resources to mount and sustain an independent Type 1 response, especially large ones like I am describing here. My role in the Bird Flu response was part of a test to determine how outside expertise might be used as part of the IMT to supplement USDA resources. The USDA split their Green Team, back-filled each half with outside contractors serving primarily in Command and General Staff Deputy roles, and deployed the two now-complete teams to Minnesota and Iowa respectively.

Another option is to borrow qualified personnel from other agencies. For example, the Coast Guard and USEPA have Federal On-Scene Coordinators (FOSCs), all warranted Contracting Officers and well versed in response management. Any government agency can reach out to those teams and likely secure the particular talent they need, such as a Section Chief or Deputy, for the duration of the response. Other available federal assets range from the military to laboratories to search and rescue teams. Many states have OSCs or Strike Teams available with similar authorities, skill-sets and resources.

The private sector usually does not have the luxury of government support and most commonly turns to contract response managers to supplement or even provide their IMT. The few firms offering this service cannot staff enough full-time resources to sustain large and relatively rare prolonged responses, and they likewise rely on networks of experienced others.

This amplifies the problem of finding qualified people on short notice, even harder to do as the response goes beyond a few weeks, as most will. Deployments are commonly up to 28 days with as little as one week between rotations. Responses can last months, making it particularly difficult for agency and corporate personnel who do not do this for a living.

Large Type 1 events will remain a challenge for government agencies and private sector responders, and it is critical to understand the need for competent IMT personnel. The IMT of the future must be able to identify and integrate talent from any available source.

Government agencies need to be prepared to reach across lines and grab expertise from other agencies, even splitting established teams and using outside talent as force multipliers (USDA in Iowa). Private sector responders must do the same with the mixed blessing of being able to access more commercial assets, but realizing that most of the large-scale IMT capabilities lie within the government.

There is an inherent quality risk in this. These are the people with whom you will go to war, at least in a metaphorical sense. You will pay a lot, but if you do it right you just might get what you pay for.

Don’t leave it to chance. Meet and vet the people you will need. Verify credentials. Many can say “I was there” or “I’ve run lots of exercises”, but only a very few can lay an honest claim to real leadership roles and the expertise and insights that will make or break your response.

Most importantly, build your team well in advance of the event. The “networked IMT” is becoming a fixture of disaster management, but because it is a niche talent, large or simultaneous events will result in fierce competition for the very limited supply of expertise. Identify and lock in your people now with the contracts, MOUs or other formal instruments necessary, because when that phone rings at 0300 and you and your people are out the door, it’s too late to start putting the team together. They should be meeting you there.